I was lucky and entrusted with big things. Is it like that now?

In my last post, I suggested the industry has a blind spot: managers are focused on project delivery to the detriment of developing young people.

This got me thinking about my rise up through the ranks. Looking back, I can’t believe how lucky I was, and I wonder if young people today are so lucky.

We’ve done a big survey with the Chartered Institute of Building to try and find out how they’re feeling. I’ll tell you about that in a minute, but first, here’s a bit of what happened to me.

One ‘O’ level

I left school at 16, with one ‘O’ level in art.

I didn’t have a clue what I wanted to do, except I was determined not to go down a coal mine or work in the ship yards.

I was keen on golf, and played with a guy called Bill, who was resident engineer on a big project in the north east at the time.

He offered me a job as a trainee civil engineer, and promised to send me to college one day a week.

I worked under Bill for a year, making tea and getting his fish and chips, and then one day he said he was leaving and that I’d have to find another job.

That was a shock, but he gave me a great reference, which got the ball rolling.

Loads of mistakes

Next, I found myself in an interview with Mike, then a contracts manager at Taylor Woodrow. He was a keen golfer, too, so I got the job.

From then on he looked out for me, and as he progressed up the ladder, so did I.

Taylor Woodrow put me on just about every course going, and challenged me with just a little more responsibility than I was comfortable with, so I was continuously stretched.

I worked hard, made loads of mistakes, and overcame most of them. I was a tryer and they liked that, and supported me.

They sponsored my civil engineering degree, which I did full time at Hatfield Polytechnic (now the University of Hertfordshire) on condition that I worked through the holidays and returned after graduation. Which I did.

They then supported me to become a chartered civil engineer and then again to become a chartered builder.

“Just get on with it!”

After 15 amazing years, mostly living in caravans on site, far from home, I left Taylor Woodrow and joined Birse Construction on the promise of a flash car, big salary, rapid promotion and projects close to home.

At that time, Birse was a young company, the fastest expanding contractor since the War. They were recruiting like crazy, people like me: driven, young, go getters just like the guys on the main board.

I joined as a “senior” project manager. On the first day I asked for my Birse tie, and was told, “We don’t have them.”

Then I asked for the company’s procedures manual, and was told, “We don’t have them either, just get on with it!”

It was like the Wild West, with loads of young blokes working like mad to get projects won and built. Energy levels were off the scale.

Never standing still

In this young, ambitious company, change was constant.

There were big improvement initiatives, strategic shifts and whole-company training programmes. If something wasn’t working, it was ditched instantly and something else was tried.

It was against this frenetic background that the board launched a company-wide transformation programme in the 1990s.

I trained up to be one of 10 internal coaches. It changed my life; I became less interested in civil engineering and very interested in people and teams.

Coach for Results

Designed with young professionals in mind

Perform better in your current role, become an effective manager and over time a great leader and together we will change the construction industry.

My new, galactic remit

After seven years at Birse I was headhunted again, this time by Wates Construction.

I joined as their operations manager in the north, but within six months the MD discovered that I had change management experience, and he asked me to lead their own company-wide improvement programme.

I had a big budget, relative autonomy, and a dedicated team. My remit was galactic: change the Organisation, and change the industry.

Around this time, the 1998 Egan Report, “Rethinking Construction”, came out and there was a genuine feeling of excitement, the sense that things could change.

Our programme was ground breaking. It won awards. It was an amazing learning experience for all concerned, especially me.

Recently, Sir James Wates acknowledged this programme, and my leadership of it, as the foundation of the Wates Group’s growth in subsequent years.

How cool is that!

Same old problems

I left Wates in 2001 to set up my own coaching organisation. My mission is to change the construction industry little bit by tiny little bit, working top down as a leadership team coach.

I haven’t succeeded, yet. There are some great leadership teams out there, pockets of excellence delivering remarkable results but, as a whole, the industry still has the same old problems.

I think these problems have actually become starker as society speeds up with technology, and gets more complex.

Which brings me back to the industry’s blind spot, which I would define as the failure genuinely to engage and develop young people, to fire them up to make the necessary changes.

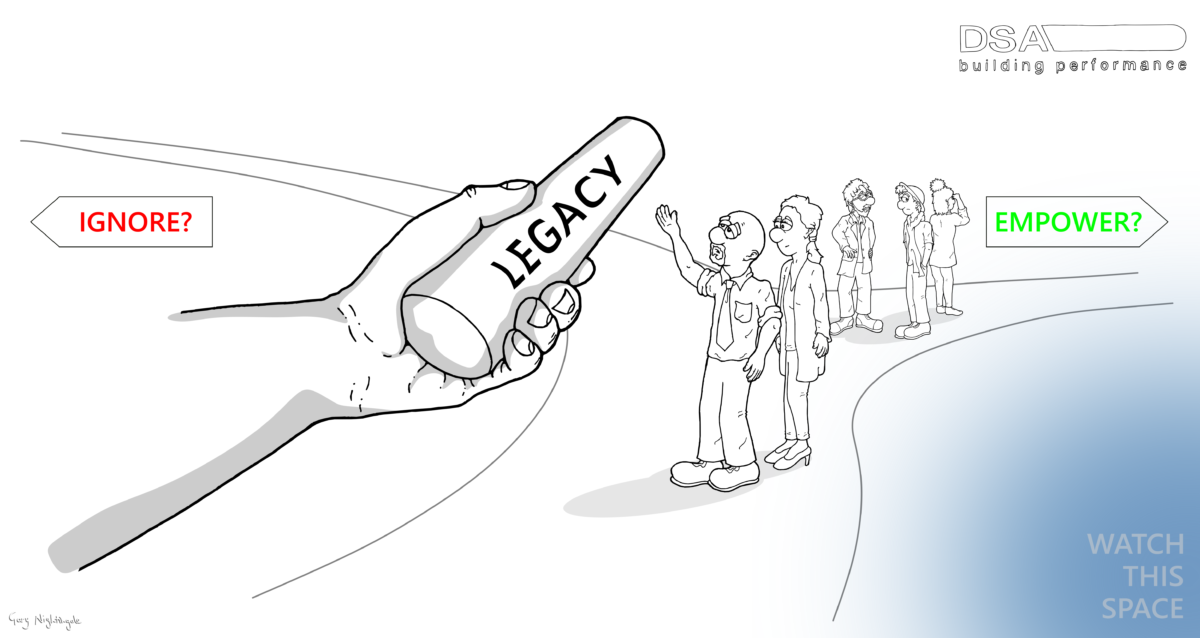

Research suggests Millennials look to their managers for guidance and development. So, we face a choice: do we ignore them as we focus on project delivery, leaving them to absorb the industry’s bad habits?

Or do we empower them – as I was so lavishly empowered – to move the industry on to a new and better place?

We are at a fork in the road, this could be our legacy.

Next step in this big idea

To understand this issue better, with help from the Chartered Institute of Building, we’ve conducted a big survey to gauge sentiment among under-40s in construction. I’m not aware of such a survey ever having been conducted before.

We’ve had 750 responses and are crunching the numbers now.

This is the next step in my big, change-the-industry-from-the-bottom-up idea: to see if their experience is like mine – sent on every course going, entrusted with leading ambitious change – or are they drifting, disaffected, starved of managers’ attention?

And, are they up for shifting this industry forward?

Watch this space!