What’s possible – revisited

“I think there is a world market for about five computers,” said Thomas Watson, the chairman of IBM, in 1943.

It’s funny, but we might let him off the hook, given it was 1943. But what about Ken Olson, president of Digital Equipment Corporation, who declared in 1977: “There is no reason for any individual to have a computer in their home”?

And if you want another chuckle, check out the words of Charles H Duell, director of US Patent Office, in 1899. “Everything that can be invented has been invented,” he said, either in a temporary failure to understand the nature of inventiveness, or because he was angling for retirement.

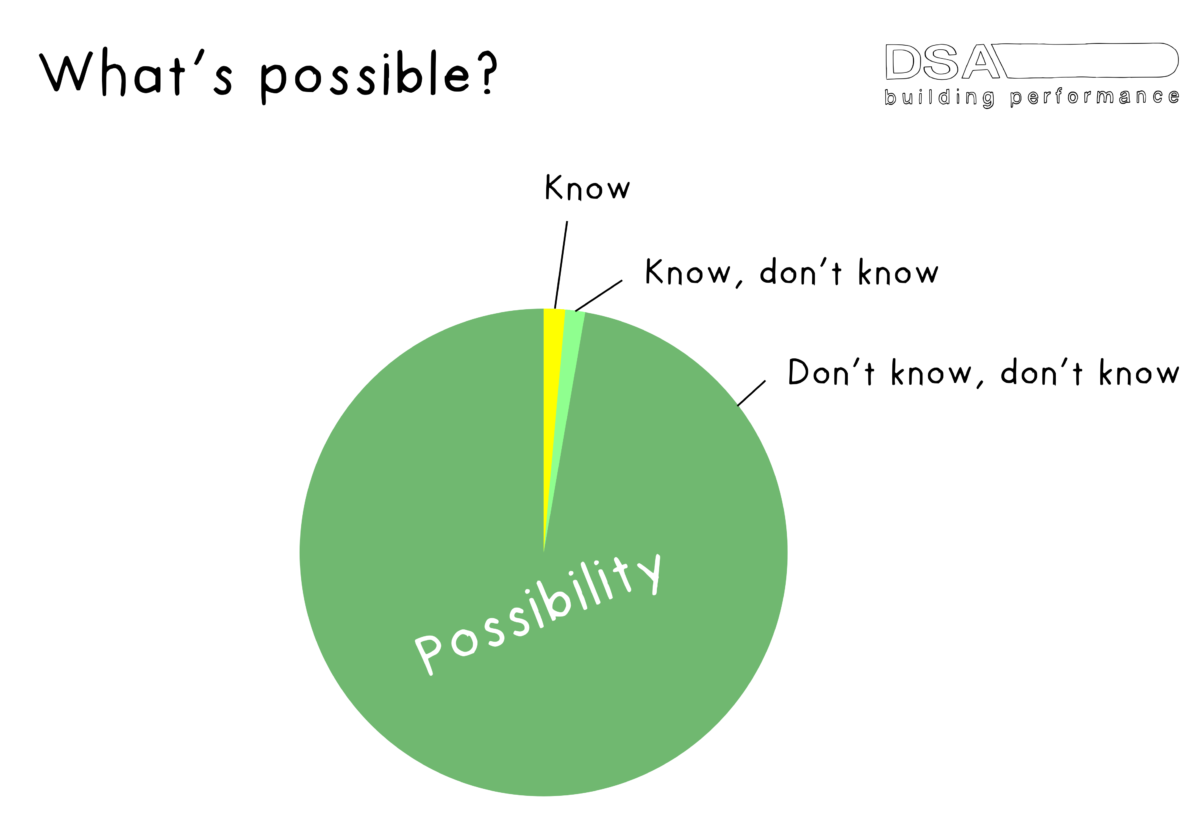

If we put all the knowledge in the world into a circle, it would be massive. What I myself know is an almost infinitesimally small bit of that circle, and it shrinks if I admit that most of what I ‘know’ is probably just opinion.

There are things I know I don’t know, such as how to sail across the Atlantic, solve a problem using differential calculus, or design a bridge to span the Thames.

If I added together all the things I know and the things I don’t know, it still wouldn’t make my bit of the massive circle of knowledge visible to the naked eye.

All that knowledge out there, which now goes completely over our heads, can be thought of as what is possible.

It’s huge, but do I live my life as if that were the case? No, I live my life as though I know it all, and I’m as prone to making silly pronouncements with just as much categorical certainty as Thomas, Ken and Charles were above.

The only way to overcome this problem is …

When politicians start a sentence with “the truth is …”, we’re conditioned to know it’s not the truth, but rather their perspective. It may be a well-informed perspective, but it’s still their perspective and there will be others.

But we’re not so discerning in work when people proclaim, “the only way to overcome this problem is …”, which is another categorical statement that is really just their perspective, and a very limited one as it’s possible that there are a million different ways to overcome that problem, we just haven’t explored them yet, probably because we don’t know what we don’t know.

And how many times, when someone is explaining something to you, do you finish off their sentence or think “I already know that”, even though when you take the time to listen carefully you discover they’re saying something slightly different to what you assumed they were saying, and you learn something new?

This happens to me every time I take the trouble to listen carefully.

How to become more appealing

If we can accept that almost everything is possible and that we know next to nothing, it changes our mindset from fixed to growth, from scarcity to abundance, from “that’ll never happen round here” to “well, that’s possible, let’s give it a try”. We become more open, more inviting, more innovative and more appealing. Yes, more appealing, because know-it-alls stifle discussion and shut down thinking to big themselves up, and nobody likes that.

When I was a civil engineer I felt as though I had to be an expert (I knew even less then!) and I had to be right. There was only one way to do the job and it was my way.

Then about twenty years ago my career started to shift and I became a coach. The joy of being a coach is you don’t have to be right. The pressure is off. You don’t even have to have a perspective.

The art of coaching, for me at least, is about listening and asking questions to explore possibilities. In hindsight, I think I would have been a better civil engineer if I had given up the demand to be right, and instead listened and asked questions to explore possibility.

The great untapped potential

If we had some humility and really worked together, we could combine our limited knowledge into something significant, something that could move us forward on our most intractable challenges, whether at project or global level. It is the great untapped potential.

How do we start doing that? Well, we could brainstorm. Here is how you do that:

- Declare intent and establish ground rules;

- Set time limit, say 15 minutes, and stick to it;

- Record ideas deliberately and quickly;

- Every idea is a good idea, met with enthusiasm;

- No discussion of an idea during the allotted time;

- Democratic selection of ideas to take forward or discard

Outmoded social technology

Our default management culture of command-and-control is about issuing orders and monitoring compliance. It keeps everyone down. “I don’t want your ideas, just do what you’re told,” it says.

A big problem with it is that the people giving orders are just as limited in their knowledge as Thomas, Ken, Charles and I were and are.

A coaching style of management understands this. Instead of giving orders, it invites people to find their own way forward. The coach-manager solicits their views and respects them.

This makes the knowledge in the room go up, and people, now feeling psychologically safe, can be candid.

My Coach for Results course is now in week six. I’m setting out to train thousands of young professionals in a coaching style of management and to build psychological safety, one conversation at a time.

At scale and over time, this will bring people together so they can share what they know, multiply intelligence and do more of what’s possible.

I see command-and-control as an outmoded social technology that has not kept pace with the advances in physical technology our illustrious know-it-alls above could never have dreamed of. I also believe the widening gap between physical and social technology explains why we can’t keep up, why we feel we’re falling behind and must work ever harder, longer and faster.

A coaching style of management is the update we need.