Leading with emotion: tap into your team’s brain science

It’s time to think ‘primitively’ to help address fear and anxiety across the workforce

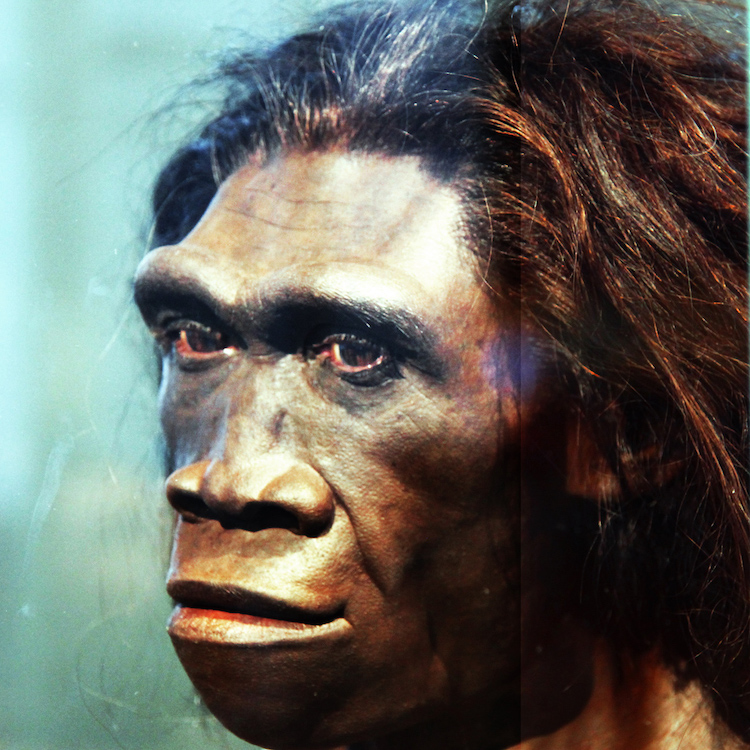

Say ‘hi’ to Sally (pictured below). That’s what I’m calling her, anyway. She may be nearly two million years old, but she’s a lot like us.

‘She’ is not a real person, exactly. The face you see is a reconstruction by paleo-artist John Gurche. It was one of seven exhibited at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

The reconstruction is based on the skull of an adult female member of the species Homo erectus, which lived in Africa, India, China, the Caucasus and other places between 1.9 million and 70,000 years ago. They were around for a lot longer than us, Homo sapiens. We only started showing up around 300,000 years ago.

It’s not known for sure yet whether we evolved directly from Sally’s kind, but many scientists agree that we are related.

They used tools and cooked their meals. They had similar body proportions to us, although their brains were about 25% smaller than ours.

Just like us, Sally would likely have picked up her children and sprinted from fire or flood. And if anyone or anything threatened her and her young, she’d likely have run or turned to fight.

Evolution of our brain

Whether our brains evolved from Sally’s directly or not doesn’t really matter. It is believed that both our brains evolved from much, much older brains, going back to the emergence of mammals some 200 million years ago, and even before that, to reptiles.

Some scientists believe we actually have three brains, developed over the main stages of our evolutionary history.

The first is our reptilian brain, which controls vital functions like breathing, balance and heart rate. Then, when we were mammals, we developed our second brain system on top of the first.

It’s called the limbic system, and it includes ancient and mysterious things like the amygdala and the hippocampus, which produce emotional responses to sensory inputs, and also responses to memories and associations. Our strong fight-or-flight instinct, provoked by fear and stress, is rooted in this layer.

Third and late to the party is the neocortex, the two big, cerebral hemispheres responsible for language, abstract thought, logic and reasoning. Sally would have had one of these, though not one as developed as ours.

People in construction have feelings too

So, what does this have to do with leadership? In my experience, business leaders think they can work exclusively with the neocortex – literally the ‘new bit’ – and ignore the older limbic system, our ‘mammalian brain’. But they can’t.

I found this out myself. I trained as an engineer, and engineering is all about the application of rational processes. That, and lots of detail.

When I first got promoted to a business leadership role, I thought my job was to be ‘Dr Spock’, the most rational person around with the best grasp of the detail.

Later, I worked out that, to deliver difficult projects, my job was actually to get people on board. But how do you do that?

Approaching it cerebrally, I calculated what was in it for the people I needed on board and presented well-reasoned arguments.

But as often as not, it didn’t work. People would pay lip service, but then passively or actively resist. It really hacked me off. Were they stupid, I wondered?

For a long time, I was flummoxed by this, until I read a book called Brain Rules by John Medina. He talked about our ‘three brains’, and observed that we process change in a certain order:

1. Emotions

2. Meaning

3. Details

Suddenly, it made sense. Leadership is all about provoking change, but people experience strong emotions when confronted with change: excitement for some, but fear and anxiety for many.

We resist change. It’s one of our survival mechanisms and links back to preserving ‘what works’ in the quest for food, shelter and security.

Think ‘primitively’ to evoke positive change

We like to think we’re like Spock, and we can be, but we’re also a lot like Sally. If you think of the evolution of the brain since Homo erectus as a 200-page book, the first 198 pages would be us as hunter-gatherers, dealing daily with starvation, exposure, lions and hostile groups.

The domestication of animals, around 11,000 years ago, occurs on page 199. Writing, in the form of Egyptian hieroglyphs, around 5,500 years ago, pops up halfway down page 200.

And us as job-holding, car-driving, screen-tapping world citizens would be the final full stop, or part of it. Biologically, we are still hair-trigger, fight-or-flight machines.

Room must be made for emotions, because they have lives of their own. If they’re expressed and recognised, they release their grip and people can get beyond them. If they’re quashed, they fester.

If you say to people faced with change: “Don’t worry! I’ve got it all figured out!” and try to explain why their fears are unjustified, you’re quashing their emotions. You may win the argument, in which case people may go along with you intellectually for a while. But you’ll have minds, not hearts.

There are two ways to apply this to our work in construction:

- Communicate change with emotions first – checking how people are feeling at the start of a meeting, then deciding meaning before getting into the detail, would create better communication all round. Diving into detail at the start is bad practice and most people would be wondering: “What’s this really about?” and leave feeling hacked off – that’s a meeting the wrong way round.

- Challenge the pressure to motivate by fear – particularly relevant at this time with much talk about regulation, enforcement, competency frameworks and threats of dire consequences for those coming up short – in an industry struggling with a perpetual skills shortage and male suicide. All of our ‘solutions’ are subject to the laws of unintended consequences, as is often the cause of our problems.

A version of this article was recently published in CIOB People

Another great and insightful post, thank you Dave. I will be trying out the ‘three stages of change’ model the next time I want to introduce something new!